Dragon Quest

| Main series games | |

|---|---|

| Dragon Quest | |

| |

| Developer(s) | Chunsoft |

| Publisher(s) | JP Enix NA Nintendo |

| Designer(s) | Yuji Horii Kōichi Nakamura Yukinobu Chida |

| Artist(s) | Akira Toriyama |

| Composer(s) | Kōichi Sugiyama |

| Series | Dragon Quest |

| Platform(s) | Famicom/NES, MSX, NEC PC-9801, Sharp X68000, Super Famicom, Game Boy Color (hybrid cartridge), Mobile phone, Wii, Android & iOS, PlayStation 4, Nintendo 3DS, Nintendo Switch |

| Release date(s) | Nintendo Entertainment System JP May 27, 1986 NA August 1989 MSX2 JP November 21, 1986 MSX JP December 18, 1986 Super Famicom JP December 18, 1993 Game Boy Color JP September 23, 1999 NA September 27, 2000 Wii JP September 15, 2011 Android & iOS JP November 8, 2013 NA September 11, 2014 EU September 11, 2014 AUS September 11, 2014 Playstation 4 & 3DS JP August 10, 2017 Nintendo Switch JP September 27, 2019 NA September 27, 2019 EU September 27, 2019 |

| Genre(s) | Console role-playing game |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

| Rating(s) | ESRB: E (Everyone) (GBC) |

| Media | NA 640-kilobit NES cartridge JP 512-kilobit Famicom cartridge GBC/SFC/MSX cartridges |

Dragon Quest (ドラゴンクエスト Doragon Kuesuto) is the original Dragon Quest game which preceded the entire Dragon Quest series. It was developed by Enix and released in 1986 in Japan for the MSX and Famicom consoles. The game was localized for North American release in 1989, but the title was changed to Dragon Warrior to avoid infringing on the trademark of the pen and paper game DragonQuest. The North American version of the game was greatly improved graphically over the Japanese original, and added a battery backed-up save feature and 5 password systems, whereas the Japanese version used a password system. Nintendo was impressed with the Japanese sales of the title and massively overproduced the cartridge; the end result was that Nintendo gave away copies of Dragon Warrior as an incentive for subscribing to Nintendo Power, the company's in-house promotions magazine.

Dragon Quest was the first turn-based role playing game to debut on a video game console and is considered a pioneer in the development of the genre. Dragon Quest's immense success proved that RPGs had a place in the industry, and would spawn a successful franchise that would become one of the de facto standards for role playing video games.

Plot[edit]

The wicked Dragonlord has kidnapped the fair Princess Gwaelin and stolen the Sphere of Light, throwing the kingdom of Alefgard into turmoil. The Hero, a descendant of the legendary saviour Erdrick, is called on by King Lorik of Tantegel castle to rescue his daughter and retrieve the Sphere of Light to save Alefgard from the Dragonlord. To do this, the Hero must retrieve several artifacts spread all across the country, including the sword, armour, and heirloom of his ancestor. The Staff of Rain and Sunstone must also be retrieved to build the Rainbow Bridge, which allow the Hero to enter the Dragonlord's Castle.

Characters[edit]

- The Hero: A descendant of the Erdrick, whose history is unknown.

- Erdrick: The legendary ancestor of the Hero. He rescued Alefgard centuries earlier from a wicked demon, and had left items and clues for his descendant to aid in defeating future threats to the land.

- King Lorik: The king of Tantegel, and ruler of the land of Alefgard.

- Princess Gwaelin: The beloved daughter of King Lorik. Abducted by the Dragonlord to break the spirits of the people and imprisoned in the Quagmire Cave southwest of Kol.

- Dragonlord: The villain of the story, he has stolen the Sphere of Light in order to infest Alefgard with horrid monsters.

Gameplay[edit]

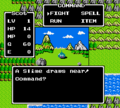

Dragon Quest is set on a sprawling overworld with towns and dungeons to be explored throughout. The player selects actions from a menu, including talking to NPCs (non-player characters); opening doors; and opening treasure chests. The towns have inns where the player can rest to restore their HP and MP; and shops to buy weapons, armor, and items from. Most NPCs give useful information to help the player progress.

The battle system is turn-based, with enemies seen in a first-person perspective. As in the overworld, the player selects actions from a menu, including attacking; casting magical spells; using items; and attempting to flee the fight.

Differences from later games[edit]

- The stat improvement algorithms depend on the player's name, deciding if the player will be more proficient in Strength, Agility, or magic (MP).

- There is no party, only a single player character.

- Although his sprite changes when the princess is rescued, to show him carrying her, the princess does not participate in any battle.

- Enemies attack the Hero 1-on-1, never in groups.

- There are no vehicles; one can only traverse the overworld map on foot, or by using a chimaera wing or Zoom spell to travel to Tantegel Castle.

- The player can only save their game by speaking to King Lorik. As such, the Zoom spell can only return to Tantegel]]. This is because the spell's Japanese name, rura, derives from the English word Ruler.

- Acquired weapons, armor and shields will automatically replace the previous item, which is then discarded or sold to the store. This is changed in the remakes.

- Keys are disposable and break when used; new ones can be purchased at one of the "key houses" in Tantegel, Rimuldar, or Cantlin.

- There are separate shops for buying holy water, unlike later games where it is sold in item shops.

- Caves are dark, and must be lit up with a torch or the Glow spell. These have limited range, which diminishes as the spell or torch wears out. The range is effectively reduced in the remakes, since the scale of the caves is larger, but the range is not increased to compensate.

Development[edit]

The genesis of the game that would become Dragon Quest took place in 1983, when the fledgling video game publisher Enix announced that it would host a national programming contest with a prize of ¥1,000,000―a value of over $21,000 in 2024―as well as the option for the amateur programmers to have their titles professionally released. Yuji Horii had been programming his own games as a hobby during this period in his life, and on a whim decided to enter what he considered to be his most accomplished work: Love Match Tennis (ラブマッチテニス). Later when Horii arrived at the awards ceremony to report on the event, he was shocked to discover that his tennis game had earned him second place. The awards ceremony was also the fateful day when Horii met Kōichi Nakamura, who won first place with Door Door (ドアドア) and was only in his junior year of high school at the time. The two became fast friends and began publishing their work through Enix, with Horii's first commercial success being the murder mystery title Portopia.

October of that same year would see Horii and Nakamura travel to the Applefest, along with Enix director Yukinobu Chida. It was here that all three men would first encounter the concept of the RPG genre through the titles Ultima and Wizardry. The younger men quickly became enamored with the two titles, having never encountered games where success was dependent on the player's strategy rather than quick reflexes, and upon returning to Japan Horii would purchase a compatible machine to play the games. Concurrent to this was the release of the Famicom in July of '83, which quickly made waves in the consumer electronics industry as an affordable alternative to the traditional computer. Enix would experiment with the new hardware by publishing a port of Portopia programmed by Namakura and marked the first time that he and Horii collaborated on commercial software.

The porting process of the mystery game laid the groundwork for the command menu that would be the cornerstone of Dragon Quest's user interface. Portopia required players to type out commands on a keyboard in order to interact with the software, but this was impossible on the four-button controller of the Famicom. Instead players would maneuver through the game via a list of commands that appeared from a drop-down menu upon pressing the A button, which listed every action the protagonist of the game could take and insured that the player would not get stuck due to forgetting the commands for key actions. This user interface method was actually first used in The Hokkaidō Serial Murder Case: The Okhotsk Disappearance (オホーツクに消ゆ), released in 1984, but is commonly attributed to the Famicom version of Portopia due to the greater number of units sold.

Released on November 29 1985, the Famicom iteration of Portopia stood out among the plethora of action titles the console had become known for due to it's focus on story and deductive reasoning, providing a distinctly unique type of challenge then what the average consumer had experienced up to that point. Sales of Portopia were also aided by the explosive popularity of Super Mario Bros, released earlier that year on September 13. The Italian adventure drove the sales of the hardware through the roof and confirmed that console-based video games were not a passing fad, with the combination of their own dark horse title's success and the growing market created by Super Mario Bros. encouraging Horii and Nakamura to bring the RPG genre they loved to the Famicom.

Formal development on the title began the same month of November through Nakamura's development studio Chunsoft, with a staff of five men over a span of five months[1]. The goal of the project was to combine the best aspects of computer RPGs while also streamlining the obtuse gameplay systems that prevented the genre from reaching a wider audience; even Ultima and Wizardry were only able to sell approximately 20K and 24K units in 1982[2]. To this end it was decided that the game would utilize the bird's eye view world map of Ultima for it's own field screen as well as in dungeons, giving players more spacial awareness than the first-person dungeons that were the genre standard at the time. Owing to the praise of the system in Okhotsk and the Famicom Portopia, the command menu was also applied to the game and written in the simplest terms to make it clear to players what actions he or she could perform at any time[3]. In addition, the dialogue of the game was written in such a way for the player to deduce how to progress through the adventure simply by talking to the cast of characters. Said dialogue was often humorous in a way not commonly seen in games at the time, such as the Puff-Puff scene of Kol, thus injecting a strong sense of personality into the scenario and contrasting the other RPGs that focused exclusively on combat and exploration. Granting the player the option to not rescue Princess Gawelin and to accept the Dragonlord's ominous offer of half the world also added a high degree of player agency, aiding in the immersion into the game's world.

The greatest challenge in the game's development was working with in the confines of the 64 kilobyte ROM capacity, which necessitated the truncating of several aspects to fit the project into the cartridge. This included the scrapping of the traditional party of heroes for a single player character, limiting the selection of items to just 15, and only being able to display a single enemy in battle[4]. Even the language of the game was affected, limited to a mere 18 katakana instead of the full set of 50 to display the text[5], and the exclusion of sprites showing characters walking from side to side and thus having the cast always face the player even while moving. Animation for monsters was also excluded due to this limited space, with the compromise being that the screen would shake when the player is attacked.

Special consideration was given to younger players, whom Horii knew would have no familiarity with RPGs at all. To this end the opening portion of the game was crafted so that the player would stand in the throne room of Tantagel castle: in order to progress from this screen, the player will have to speak to []King Lorik]], open a treasure chest to retrieve a key and use it to open the chamber door, and then use the stairs command to descend to the ground floor of the castle―every action necessary to traverse the game's overworld is conveyed to the player in a single, unobtrusive moment[6]. To teach younger players the importance of leveling up and becoming stronger, the threshold for reaching level 2 was dropped from 20 Experience points to just 7[7]. In addition the penalties for losing a battle were greatly reduced compared to computer RPGs, with players only losing half their gold and being sent back to King Lorik instead of suffering a game over that voided all of their gold and Experience points and thus wasting the time spent playing the game[8]. The presence of the status screen was implemented at Yukinobu Chida's request, who insisted that all information pertaining to the Hero's capability be conveyed to the player when it was obscured in computer RPGs. His basis for this argument was an incident after the Famicom release of Portopia, where elementary-aged children called Enix to ask for tips. Chida could overhear the children happily chatting with the Enix representatives during these calls, leading him to conclude that video games were not just entertainment, but a communication tool for people. As such he insisted that the Hero's capabilities be displayed via the status command, certain that children would discuss which areas of the game could be explored at a given level and thus increase the word of mouth amongst the target demographic[9].

Chida was also responsible for involving maestro Kōichi Sugiyama with the project. Sugiyama had witnessed the emergence of technology in the music industry over his career and became interested in computers as a result, purchasing a PC-8801 in the early 80's to experiment with and subsequently developing a hobby for playing games. An Enix title called Kazuo Morita's Shogi (森田和郎の将棋) caught his interest at one point, and Sugiyama filled out the customer feedback questionnaire in a cheeky manner for fun. Leaving the card on his desk as he left for other business, his wife Yukiko would slip it into the family mailbox as she stepped out to go grocery shopping[10]. The questionnaire was presented to Chida, who was shocked to see that the celebrity had written his answers in hiragana like an elementary school student, and an Enix representative was quickly dispatched to Sugiyama's home to negotiate a working contract for the company: Sugiyama was officially hired on to compose the music for Wingman 2: The Resurrection of Kitaklar (ウイングマン2 -キータクラーの復活).

As Dragon Quest was in development at the same time as Wingman 2, Chida proposed having Sugiyama compose the music for the title as well as he felt the score provided by Chunsoft was inadequate. This decision was met with harsh resistance by Nakamura and Chunsoft though, as the group of men in their 20's were certain that a man in his 50's would not be able to write suitable music for a video game. Horii was not opposed to Sugiyama's involvement however, and he and Chida would act as intermediaries until an agreement could be reached. Sugiyama himself dissolved the tension by speaking casually to Chunsoft of the times he would drive to Yokohama after work just to play pinball, his obsessions with backgammon, and other anecdotes. The programmers would relent, coming to see Sugiyama as a fellow gamer who just happened to be a tad older[11]. The actual production of the game's soundtrack took one week to complete, with Sugiyama giving special attention to the overworld and battle themes due to how often the player is bound to hear them[12].

Development became a whirlwind of balancing adjustments near the end based on feedback provided by play testers, leading to the game's release being pushed back by one week. The changes were so drastic that monster behavior was completely restructured from the ground up, effectively leaving Chunsoft to reprogram half of the game all over again. The Hero himself was also rebalanced as he was deemed to be lagging too far behind the strength of the monsters after level 15[13].

While busy developing on the game, Horii was still taking freelance work as a writer and was working on the Famicom Shinken section of Weekly Shonen Jump magazine under the pen name of Emperor Yu (ゆう帝). Famicom Shinken was the video game section of the magazine, created by editor Kazuhiko Torishima. Horii and Torishima met years prior when introduced by their mutual friend Akira Sakuma and quickly became friends themselves, which led to Torishima learning of the development of Dragon Quest in passing. This was the news the editor needed to hear, as Shonen Jump was struggling to compete with rival magazine CoroCoro comics when it came to video game coverage, and being able to use Famicom Shinken to provide coverage on the development of a brand new title would give Jump an unprecedented advantage. Torishima convinced the skeptical management of Shonen Jump to provide page space for the unreleased and experimental title in the magazine, using his authority as the editor of Akira Toriyama to assign the rising star artist to the project as chief illustrator. The game's title screen was designed by Kazuo Enomoto, also a Shonen Jump employee, who suggested adding the silhouette of the dragon to the logo due to being in the game's title and the importance of the beasts in the game's setting. As Enomoto did not know what an RPG was at the time, he used films as a point of reference and created a title screen that resembles a wide-screen lens to replicate the cinematic effect.

Dragon Quest would first be shown to the world in the February 11, 1986 issue of Shonen Jump, which continued providing behind the scenes coverage of the game until it's May 27 release.

Legacy[edit]

Influence on the Video Game Industry[edit]

Before the release of Dragon Quest, the video game marketplace consisted of fast-paced, reflex dependent action titles. The majority of these were originally developed as arcade quarter-munchers, and retained the immense difficulty of such even when ported to a home console. Storytelling was sparse, if text was even programmed into a game, and titles relied on the player's imagination to fill in the gaps.

When Yuji Horii's dream project proved to be a smashing success, the entire perception of what a video game could be changed. Countless RPGs flooded store shelves to cash in on the newfound hype surrounding the genre, and action titles began to experiment with deeper plotlines and character interaction instead of merely pushing level complexity.

A humble title from a small publishing company changed everything for games.

Remakes[edit]

Being the original game in the series, Dragon Quest has been remade and re-released on a variety of different platforms; most notably for the Super Famicom. Most of the remakes feature localizations which differ from the original, as well as additional features such as an item/gold vault and streamlined menu system. Other changes include tweaks to the leveling system to make it easier to gain levels without excessive grinding. Most fans consider almost all remakes to be easier than the original release for this reason. See List of version differences in Dragon Quest I for a listing of version differences.

Note that only some of the remakes have been released outside of Japan. For a full list of releases and dates, visit List of games.

Broadcast Satellaview version[edit]

A special free version of the game known as BS Dragon Quest was available to play on the Satellaview peripheral during the early months of 1996. This version of the game used the art assets of the 16-bit remake, included voiced dialog for additional scenes, and additional features not seen in any other version since.

Sequels[edit]

Dragon Quest was closely followed by Dragon Quest II: Luminaries of the Legendary Line which met with similar success. Dragon Quest II featured the same timeline and setting as the original, a concept which was further extended into Dragon Quest III: The Seeds of Salvation. Together, the first three games comprise what is known as the Erdrick trilogy. All three games were designed for the Famicom/NES and share similar artistic styles.

Recurring monsters[edit]

As the first game in the series, Dragon Quest introduced several monsters that proved instant favorites among fans. In particular, the Slime, Dracky, and Chimaera are featured in almost every other game in the main series and spinoffs.

Credits[edit]

| Role | Staff |

|---|---|

| Scenario writer | Yuji Horii |

| Character design | Akira Toriyama |

| Music composer | Kōichi Sugiyama |

| Programming | Kōichi Nakamura |

| Koji Yoshida | |

| Takenori Yamamori | |

| CG design | Takashi Yasuno |

| Scenario assistant | Hiyoshi Miyaoka |

| Assistant | Rika Suzuki |

| Tadashi Fukuzawa | |

| Title screen design | Kazuo Enomoto |

| Instruction manual illustrator | Takayuki Doi |

| Special thanks | Kazuhiko Torishima |

| Director | Kōichi Nakamura |

Trivia[edit]

- The amount of time that takes place between Dragon Quest III and Dragon Quest is left ambiguous in English, but the Japanese versions imply that the latter is sixteen generations removed from the former. This is suggested by King Lorik being named as the sixteenth descendant of the original King of Alefgard.

- Although the iron helmet, leather hat, and helm of Ortega are featured in official illustrations, there is no equipment slot for helmets.

- In the original 8-bit versions there are special menu commands to climb stairs and open chests (done automatically in later games), and in the Japanese version to select directions for certain commands, since characters do not have sprites facings in these versions.

- The Japanese Famicom and MSX versions of this game and Dragon Quest II have a Spell of Restoration (password system), in place of the "Imperial Scrolls of Honor" (battery save system). The password does not save current HP and MP, or the contents of the chests. So all of these will be reset on a reload.

- Whether a treasure chest has been opened or not is never recorded through these passwords. By reloading the game, the player can collect a chest's contents multiple times.

- The American Game Boy Color release of Dragon Quest I & II changed several character and town names from the NES script to better match the original Japanese names, and to account for the limited text display space of the handheld. These changes would be reverted in the 2014 Android/iOS English release, which utilizes the names invented for the NES release with a script that is more faithful to the original Japanese than either previous version.

- A recolor of Erdrick's Sword appears in Final Fantasy XII, named Tournesol and used by the optional boss Gilgamesh.

Soundtrack[edit]

Kōichi Sugiyama served as composer for the soundtrack. He would go on to write most of the music for the entire Dragon Quest series. Dragon Quest I's symphonic suite was bundled with Dragon Quest II's symphonic suite and a disc of original compositions as Dragon Quest in Concert. Here is the track listing for the Dragon Quest I portion of that release:

- Overture March (序曲/Overture) (3:59)

- Château Ladutorm (ラダトーム城/Castle Ladutorm) (3:25)

- People (街の人々/People of the Town) (3:36)

- Unknown World (広野を行く/Going to the Plain) (2:07)

- Fight (戦闘/Fight) (2:12)

- Dungeons (洞窟/Cave) (3:40)

- King Dragon (竜王/King Dragon) (3:08)

- Finale (フィナーレ/Finale) (2:40)

Gallery[edit]

Videos[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ https://web-archive-org.translate.goog/web/20100614061622/http://plaza.bunka.go.jp/museum/meister/entertainment/vol2/?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=no

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/cgw_6/page/n3/mode/2up

- ↑ In the 8-bit original these actions are TALK, SPELL, STATUS, ITEM, STAIRS, DOOR, SEARCH, & TAKE

- ↑ なぜなら、第1作をつくるときは本当にやりたかったことをいろいろ切り捨てたんですよ。なにしろ64キロバイトしかないので、やりたいことがすべてできたわけではないんです。パーティーも1人しかできない。アイテムは15種類しかない。モンスターもこれしか出せない。こうした制約のなかでおもしろいエッセンスだけを抽出して制作したので、逆にファミコンがどんどん進化して容量が増えるにしたがって、入れたかった要素を足していったんです。だからつくっていて楽しかったですね。

- ↑ Only イ、カ、キ、コ、シ、ス、タ、ト、ヘ、ホ、マ、ミ、ム、メ、ラ、リ、ル、レ、ロ、and ン are in the game, with the hirugana characters ヘ and り also being used due to taking up less memory than their katakana counterparts

- ↑ 「戦って強くなっていくんだよ」「文字でやりとりしながら物語を体験するゲームだよ」と言うと、じつは子どものほうが興味をもつし、たとえ難しかったとしても、それを「おもしろい」と言ってくれましたね。『ドラクエ』を出すまではアクションゲームが主流だったので、どうなるのかなあという気持ちはありました。そのために、とっつきやすくなるような工夫はいっぱいしましたけどね。まずゲームの最初は、王様の部屋にとじこめられていて、とりあえずコマンドをいろいろ入れないと出られない。でも部屋を出たときには、宝箱をあけて、人と話して、ドアを開けて、階段を降りるといった、ゲームに必要なコマンドをだいたい覚えられるようにしたんです。

- ↑ 戦闘になれば、相手が襲ってくるので「たたかう」を押していればいい。そうすれば経験値があがって、レベルアップして、どんどん強くなっていく。早い段階ですぐレベルアップするようにして、強くなることが気持ちいいっていう感覚を味わってもらいたかった。

- ↑ HIPPON SUPER編集部・編『ドラゴンクエストIV MASTER'S CLUB』(JICC、1990年)pp.4-9 堀井雄二インタビュー

- ↑ PCでのRPGのプレイに慣れていた堀井や中村は、開発中の『ドラゴンクエスト』のレベル表示について「レベルの強さはいつでもコマンドで見られる」「自分が今レベルいくつかはだいたい分かる」と主張し、ウインドウ内の表示を出来るだけ少なくして、画面を見やすくすることを提案した。しかし、それに対して千田は「レベル表示は絶対必要だよ」と反論。千田の弁によると、『ポートピア連続殺人事件』が発売されたばかりの頃、エニックスに小学生のプレイヤーから質問の電話がかかってきて、電話の向こうでわいわいとにぎやかに楽しんでいる声が聞こえてきたという。それを体験した千田は、「ファミコンはパソコンのようにひとりで遊ぶゲームではない」「ゲームセンターのようにみんなでワイワイやりながら遊ぶ、パソコンとは異なるコミュニケーションメディアだ」と力説。それを聞いた堀井と中村は、「なるほどコミュニケーションメディアですね」と返答し、その提案を受け入れることになった。Source: ドラゴンクエストへの道 page 129~133 ISBN 978-4-9005-2726-3

- ↑ "(笑)。そのアンケートはがきには 「終盤は強いけど、序盤の駒組みがイマイチ」みたいに、 ちょっと生意気なことを書いて、 そのままほったらかしにしておいたんです。 そしたら、たまたまうちのカミさんが それを見つけて、買い物に行く途中に ポストに放り込んだみたいなんです。" https://archive.fo/pz7E3

- ↑ ニンテンドードリーム2005年11月号

- ↑ すぎやまこういち VS 田尻智」『ドラゴンクエストIV マスターズクラブ』JICC出版局、1991年2月10日、13頁。ISBN978-4-7966-0084-2。

- ↑ Source: ドラゴンクエストへの道 page 234 ISBN 978-4-9005-2726-3